This blog was written during the Scottish referendum in Britain. Also see The British Isles Happy Family

I worked for the Institute of Physics - a UK and Ireland body – for almost thirteen years. My role as Representative was specifically to work for the IOP in Ireland - one of the ‘nations and branches’ in the organisation. Since IOPI was an all-Ireland body representing both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, my work had both an east-west international dimension (Ireland-UK) and a north-south dimension (Ireland-Northern Ireland). Working for a two-country organisation meant that there were times when one was in a twilight zone, politically straddling many vested interests, and not always sure about how far one could push the ‘Irish’ factor. Suffice to say that on a few occasions I was known for the stubborn Irish hat I had firmly set on my head. A gentle reminder once (to a colleague) that Dublin was in the Republic of Ireland and not in Northern Ireland was at the milder end of the scale. An escalating trail of angry email exchanges where I insisted that the style rules could and should be bent to allow the President of Ireland to be written with a capital ‘P’ (despite what the Oxford English Dictionary dictated) was at the other end of the scale. If the same house style guidelines ruled that The Queen was always to be written with both a capital t and a capital q – then surely our president could have a capital p?

Given this complicated background when I was offered an opportunity to make a presentation to staff at the headquarters of the organisation in London, I couldn’t resist making it a history lesson on Ireland for the predominantly British audience. An edited extract from the speech I made follows with the last paragraph added as a contribution to the imminent Scotland independence vote.

Dear United Kingdom

By way of introduction, come on a drive with me from Dublin to Belfast. It is extremely hard to tell when you are crossing the border and moving from Ireland into Northern Ireland – you don’t have to bring your passport or show ID. One of the main ways of telling that you have crossed the border is that the speed signs change from kilometres per hour to miles per hour (and if you are in an Irish car that gives its speed only in Km/h (all cars since 2006) you have a problem. You have to multiply your speed in kilometres by five and divide by eight (while driving) to see if you are keeping to the correct speed limit in miles per hour. Somewhat dangerous and challenging!

Meanwhile most things are familiar – you are still driving on the left, the countryside is similar - undulating hills of green broken up with hedges, trees, houses and farms. However the road markings are altered a little with road signage on a different coloured background. A post box that slips by is red, not green; RTE 1 on your radio goes off the air and you find, suddenly, you are tuned into BBC Radio 2. And if this was number of years ago Terry Wogan’s dulcet Irish-but-British tones have replaced Pat Kenny’s posh Irish accent, confusing you even further. Next your mobile phone beeps with a message saying that ‘calls home or in EU for 52c/min & 23c/min to receive inc VAT’; and a few minutes later you stop for petrol and find that you forgot to bring sterling with you. They take euro but you wonder if the rate was fair, and suddenly it all begins to feel more foreign than familiar. You mentally have to kick yourself noting that you have actually driven into a different country. Exactly the same thing happens for the Belfast native driving to Dublin – but in reverse – and the speed problem doesn’t present itself quite so scarily as all British cars still display both kilometres and miles per hour on their speed dials.

When the founding group first met in 1964 to form the Irish ‘branch’ of the Institute of Physics, it was decided that it would remain as a society covering the whole island of Ireland and avoid political considerations. The physicists present decided (in a Father Ted like way) that they were, “above that sort of thing.” However the political reality of running the institute on the island of Ireland was not without disputes. In the late sixties there were some heated discussions about having equal numbers of representatives from north and south on the committee. During the debate one Northern Ireland committee member made a plea to another committee member from Trinity College Dublin (who was born in England), ‘We English must stick together’ and the Trinity member replied ‘I don’t know about you, but I’m not English I was born in Yorkshire!’

The Republic of Ireland is a description (1948 Act) and not the name of the sovereign state of Ireland. Ireland (in English) and Éire (in Irish) remain its two official names. But Éire – which was the word originally used to describe the island of Ireland when it became a free state is now rarely used in day-to-day conversation (apart, it seems, from football pundits in the UK!). Generally the Irish don’t like Éire being used by others to describe our country - Irish history and politics are at play here but the analogy is using the word Deutschland for Germany during a conversation in English. And furthermore this dislike of the use of the word Éire is contrarian and confusing when you find Éire written on all Irish postage stamps; Éire inscribed on all Irish coinage (including Irish euro coins); and both Éire and Ireland written on our passports and official state documents since 1937 when the Republic was formed.

Moving to the Britannia side of things the terms Great Britain, The United Kingdom, The British Isles and British Islands all mean something different – but for political purposes British passports all have The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on the front. This official name, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, came into use in 1922 after the Irish Free State was formed.

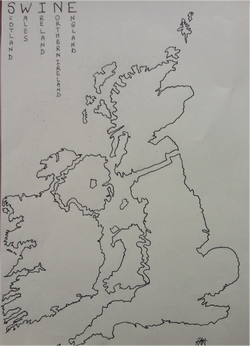

If the union was to break up completely what might the future hold for us on these British Isles? Uniting Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Northern Ireland and England under a federation could give us the rather wonderfully titled – The Democratic union of S.W.I.N.E. But that is probably a step too far; so, in the interim, may I invite all the nations of the union to start embracing change by measuring your miles in kilometres to make things easier for all of the Irish, Germans, French, Italians, Spanish, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Polish (and more) who love to visit your country in their cars – but cars which can only measure their speed in kilometres per hour. And fear not United Kingdom - It won’t be the slippery slope to the Euro as so many of you might fear. As any physicist or mathematician will tell you, a kilometre will always be a million miles away from a euro.

Love from Ireland xx

© Alison Hackett 07 Sept 2014

Illustration by Alison Hackett –drawn by hand so not an accurate representation.

Given this complicated background when I was offered an opportunity to make a presentation to staff at the headquarters of the organisation in London, I couldn’t resist making it a history lesson on Ireland for the predominantly British audience. An edited extract from the speech I made follows with the last paragraph added as a contribution to the imminent Scotland independence vote.

Dear United Kingdom

By way of introduction, come on a drive with me from Dublin to Belfast. It is extremely hard to tell when you are crossing the border and moving from Ireland into Northern Ireland – you don’t have to bring your passport or show ID. One of the main ways of telling that you have crossed the border is that the speed signs change from kilometres per hour to miles per hour (and if you are in an Irish car that gives its speed only in Km/h (all cars since 2006) you have a problem. You have to multiply your speed in kilometres by five and divide by eight (while driving) to see if you are keeping to the correct speed limit in miles per hour. Somewhat dangerous and challenging!

Meanwhile most things are familiar – you are still driving on the left, the countryside is similar - undulating hills of green broken up with hedges, trees, houses and farms. However the road markings are altered a little with road signage on a different coloured background. A post box that slips by is red, not green; RTE 1 on your radio goes off the air and you find, suddenly, you are tuned into BBC Radio 2. And if this was number of years ago Terry Wogan’s dulcet Irish-but-British tones have replaced Pat Kenny’s posh Irish accent, confusing you even further. Next your mobile phone beeps with a message saying that ‘calls home or in EU for 52c/min & 23c/min to receive inc VAT’; and a few minutes later you stop for petrol and find that you forgot to bring sterling with you. They take euro but you wonder if the rate was fair, and suddenly it all begins to feel more foreign than familiar. You mentally have to kick yourself noting that you have actually driven into a different country. Exactly the same thing happens for the Belfast native driving to Dublin – but in reverse – and the speed problem doesn’t present itself quite so scarily as all British cars still display both kilometres and miles per hour on their speed dials.

When the founding group first met in 1964 to form the Irish ‘branch’ of the Institute of Physics, it was decided that it would remain as a society covering the whole island of Ireland and avoid political considerations. The physicists present decided (in a Father Ted like way) that they were, “above that sort of thing.” However the political reality of running the institute on the island of Ireland was not without disputes. In the late sixties there were some heated discussions about having equal numbers of representatives from north and south on the committee. During the debate one Northern Ireland committee member made a plea to another committee member from Trinity College Dublin (who was born in England), ‘We English must stick together’ and the Trinity member replied ‘I don’t know about you, but I’m not English I was born in Yorkshire!’

The Republic of Ireland is a description (1948 Act) and not the name of the sovereign state of Ireland. Ireland (in English) and Éire (in Irish) remain its two official names. But Éire – which was the word originally used to describe the island of Ireland when it became a free state is now rarely used in day-to-day conversation (apart, it seems, from football pundits in the UK!). Generally the Irish don’t like Éire being used by others to describe our country - Irish history and politics are at play here but the analogy is using the word Deutschland for Germany during a conversation in English. And furthermore this dislike of the use of the word Éire is contrarian and confusing when you find Éire written on all Irish postage stamps; Éire inscribed on all Irish coinage (including Irish euro coins); and both Éire and Ireland written on our passports and official state documents since 1937 when the Republic was formed.

Moving to the Britannia side of things the terms Great Britain, The United Kingdom, The British Isles and British Islands all mean something different – but for political purposes British passports all have The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on the front. This official name, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, came into use in 1922 after the Irish Free State was formed.

If the union was to break up completely what might the future hold for us on these British Isles? Uniting Scotland, Wales, Ireland, Northern Ireland and England under a federation could give us the rather wonderfully titled – The Democratic union of S.W.I.N.E. But that is probably a step too far; so, in the interim, may I invite all the nations of the union to start embracing change by measuring your miles in kilometres to make things easier for all of the Irish, Germans, French, Italians, Spanish, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Polish (and more) who love to visit your country in their cars – but cars which can only measure their speed in kilometres per hour. And fear not United Kingdom - It won’t be the slippery slope to the Euro as so many of you might fear. As any physicist or mathematician will tell you, a kilometre will always be a million miles away from a euro.

Love from Ireland xx

© Alison Hackett 07 Sept 2014

Illustration by Alison Hackett –drawn by hand so not an accurate representation.