I first met Arnie in the RDS the time I was running a poetry Valentine’s Day event in2019 — Date with a Love Poem. Guests came to a coffee morning to listen to love poems old and new being read by a group of contemporary poets. Not long afterwards Arnie joined the writing group I was running and we quickly reached the second base of trust as a couple of poets exchanging feedback on our poems. In tennis and golf you need the right sparring partner — it’s the same in poetry.

Arnie’s journey is intriguing. Whose isn’t? His grandmother had three husbands: "The first one binged on Sugar Creek,/gave credit to Negroes,/went bankrupt,/threatened suicide,/died of drink." And by the end of the poem, she’s on the third husband: "He was kind./It was enough."

In 1969, Arnie was one of the eligible men included in the draft lottery to serve in Vietnam due to the random fact of his birth date falling between 1944 and 1950. He was living in college accommodation on the night of the draft with his wife and young child, Nick, who is here with us today. The fact that there was so much static during the radio broadcast of the lottery must have been terrifying as he wondered if his birthday had already been called but he missed it. A fork in the road he couldn’t control. I doubt we would be here in Poetry Ireland this evening, that I would be publishing his poetry, that he would have met his wife Adèle and come to Ireland had his luck in that lottery been different. He wasn’t called to war. His poem about that draft lottery night I have workshopped with him – and many others – thus we have a second collection already in the pipe-line.

But this collection first. Some of that what-iffery is in Arnie’s knowing poem about how his and Adele’s destiny turned out. In "The Second Husband Explains It All", on page 66, he captures a sentiment not unique to Irish mothers (but oh so very Irish).

In spite of the general randomness of fate,

others could have asked, as her mother did,

less politely, are you sure you should do that,

throwing doubt under the wheels of initiative

like a hand grenade or at least a handful of nails.

Flinging down this gauntlet of responsibility

allowed the mother to admire her own reflection

in the polished surface of I told you so.

And later he imagines the what if for Adèle:

How different it would have been to pause

and risk returning to a town that whispered

she had her chance. Could she have managed

to construe whispers as flowers of forgiveness,

gentlest scorn, background noise of knowledge?

The leading art critic of the Victorian era was a man called John Ruskin. There is an art joke mocking Ruskin which I recently read about in AA Gill’s memoir “Pour Me” (Weidenfeld & Nicholson). On his wedding night it was said that “Ruskin was revolted by the pubic hair of his new bride having virginally imagined that all women were as bald as classical marble. He confused the erotic with the aesthetic, got his nude mixed up with his naked.”

Why bring this joke to a poetry launch? Because poetry that is worth reading is about the poet taking the risk of being naked, undressing, not looking to romanticise with idealised marble nudity. Arnie has undressed and allowed us to take a look. He has taken an unsparing look at his own life. Here is a man confident enough to admit in On the wing — a poem which starts out with bird watching --

sure I’ll never piss

young-man strong

again, just this

old man’s slow

resignation,

followed by

a wet spot on the pants,

embarrassment

of what I can’t hold

or wait for.

And in the Poetry of Aging he knows that “though the walls are thick,/ protective, the inside roils.” Look closely and you’ll find you’re not so different. We might wobble differently underneath the surface, but rest assured, we all wobble.

Take poetry slowly. Don’t rush. Savour the salt of the caviar when Arnie catches the eye of a black man in line being snubbed by a sales clerk in Greensboro, North Carolina: “I, shame dumb,/he, rage quiet,/refuses her/and any me.”

Taste the ambrosia of love when he is with his daughter “ma fille”, In Dijon (“she chats up my silence”). Feel grief catch in your throat in Nocturne

Grind loss coarsely, sieve it

through subtle fingers, mourn

the shell holes and foxholes.

Look for the turn, find it on a second, or a third reading. It’s there, 15-year old Arnie living in the VA town where his father worked, playing pool with a wounded veteran who had been “blown into a steel chair” a man who “called himself spic, in a tone/that made sure I wouldn’t,”

He’d rage at the game,

chalk his cue, then take me

at straight or nine ball,

without knowing that I knew

he discharged loss

in the crack of ball on ball.

This collection is one of tenderness, of no regrets, of acceptance. The collection closes with Border Crossing, with hope, in the better place he finds himself:

I stop, belly-deep

in loosestrife poor

but patient, already

in a better country.

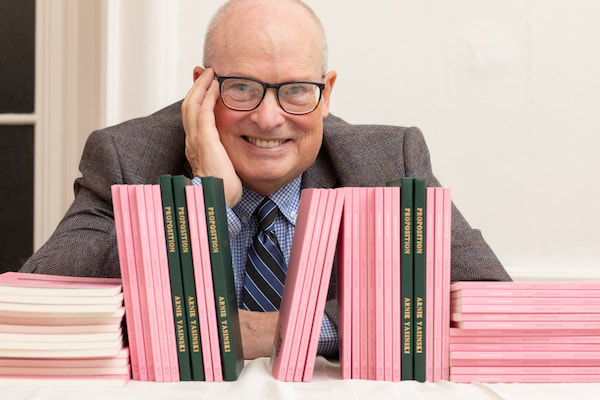

They say that publishing a poem is like giving it a decent burial. But this is no funeral, this is a celebration of a life lived, a man who has looked honestly at himself in the mirror, and is carrying on. The thing is, you are ours now Arnie. No going back to America. For presenting us with his work of art, this stage of his inner transformation, his Proposition, please express your thanks and give a warm Irish welcome to Arnie Yasinski.

Alison Hackett — this is the text read at the launch of Proposition in Poetry Ireland on 23 Jan 2020

Signed copies of Proposition by Arnie Yasinski published by 21st Century Renaissance can be purchased in Hodges Figgis, Dawson Street, Dublin 2 and on this website online