Am I a writer? I think so. Most mornings I read the paper and within a couple of articles find myself reaching for the laptop to write a letter to the editor of which ever publication I have been reading. Little did I know that my mother, too, had written letters to the papers and hoped they would be published, almost fifty years ago. I warn you. Getting published can be an addictive pursuit.

When the first letters from home arrived for me in boarding school in 1972 they were written in my father’s hand. I only recall one letter from my mother that first term. Years later I realised that she must have discovered she was ill around the time that I had started school. Her world was literally going to end. And she didn’t want to tell me. So, my father wrote to me. I still feel a tug of emotion when I see his handwriting. It was on the brown envelopes curled around the rolled-up Judy, and later, Jackie, comics he sent me every week. No one direction for his script, leaning to the right, to the left, occasionally upright – a strong and distinctive hand with a snappy sign off that always made me smile. He, and his brother, Earle, had edited the student magazine T.C.D. A College Miscellany in the forties Rooted in the classics and Shakespeare, their writing was effortless. Elegance and eloquence peppered with wry humour.

My writing was honed internally. As email communications took off – a time when I was working for the Institute of Physics – I remember sending my first email to the thrilling sound of the dial up connection. After clicking “send” a nervous realisation dawned on me that I couldn’t reach into the machine and pull it back, tear it up, or scratch it out. No second chance with a postal service that delivered at the speed of light. But I hated sending a poorly written email. Why not make it well written, well-argued and force the person reading to sit up and take you seriously? Word Perfect was a dream. We writers could edit-edit-edit exponentially faster. A whole lot easier than a Remmington and Typex. Now, I sometimes edit my poetry online. This is a changed world.

In 1997, I tried out my first writing group while my husband was working in Jena (which was in the former Eastern bloc of Germany). I had three children to mind while he was away for weeks at a time, the youngest being two and a half, the oldest ten. My brain, after seven years as a full time domestic engineer (Mother), was about to seize up. I was running out of steam with the children’s stories at bed time. Writing would tick a few boxes – get me out of the house, meet some adults and exercise my brain.

Reading out my fiction and poetry to a bunch of strangers was nerve racking. The first piece I shared was a stiff short story edited to within an inch of its life. Some people had brought fearfully unedited work complete with typos, spelling mistakes and peculiar grammar – but they had a looseness that was eluding me. Reading back some of my poems from that time I can see the problem: controlled and cool, almost academic, without feeling.

Now, having been through a four-year emotional roller coaster of delayed grief for my mother who died in 1973, I realise that poetry is a type of emotional mathematics. How to meet your readers’ imagination with your imagination, without making them feel queasy or wanting to run for the hills. Finding your voice, your tone, but always with economy. For me, clarity and truth are the most important drivers for any piece of writing.

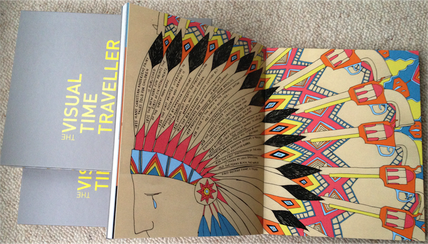

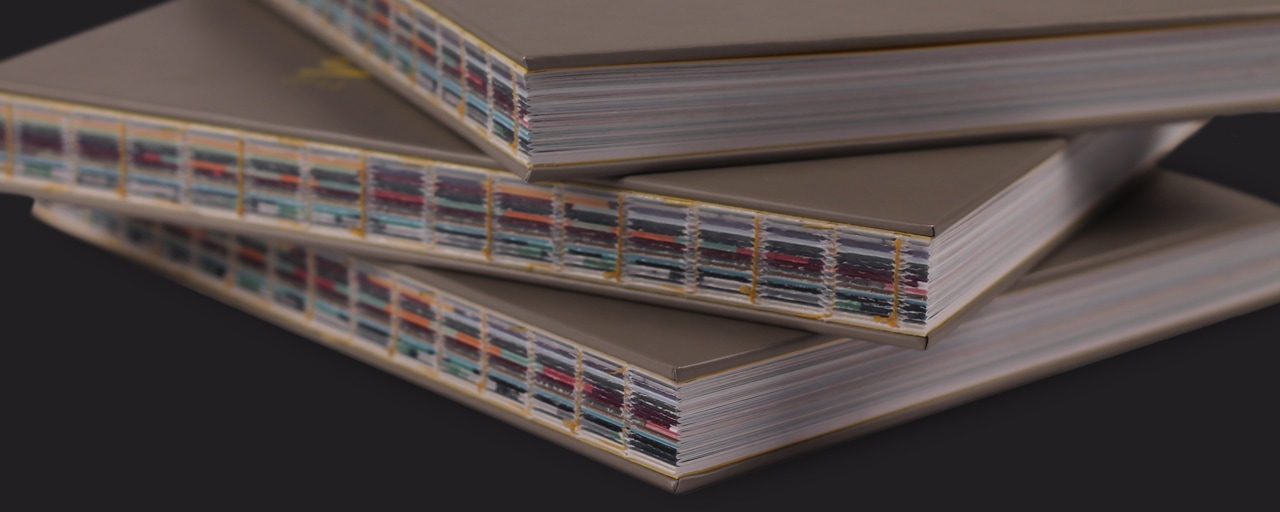

I had not expressed my grief at the time my mother died. It resurfaced in 2012 as the fortieth anniversary of her death approached. Why did I write The Visual Time Traveller during this traumatic time? It was the most beautiful thing I could create – both for her and for my frightened twelve-year-old self. A creative project with a mathematical structure (twelve facts for every five years and a design to communicate those facts) which suited me. I could escape and immerse myself in it with joy. The poetry which I started writing at that time, was far more directly connected with the grief. Most poems were written through a veil of tears as, for the first time, I faced those feelings of loss and abandonment. I printed these early ones, gave them to family and thrust them at friends. I couldn’t speak.

My father, at that time of that high emotion, wrote to me and said he thought I should publish the poems, poems which must have been hard for him to read. In another letter, he suggested that I get my hormones checked. I had dragged up the past in the most fearful way for him.

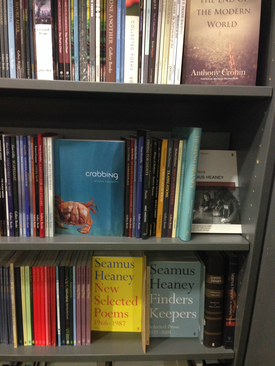

The Visual Time Traveller is for my mother, Lesley; Crabbing is for my father, Ronnie. These two publications are to honour them. But they also book-end a very significant period in my life – not only the last four years but that time from the day I turned twelve in 1973 to the present time, the year 2017. I salute you Lesley and Ronnie, my beloved flawed parents.

© copyright Alison Hackett. Posted online 28 June 2017

This article was written was first published online on the writing.ie site here

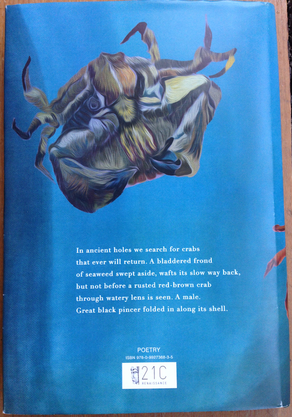

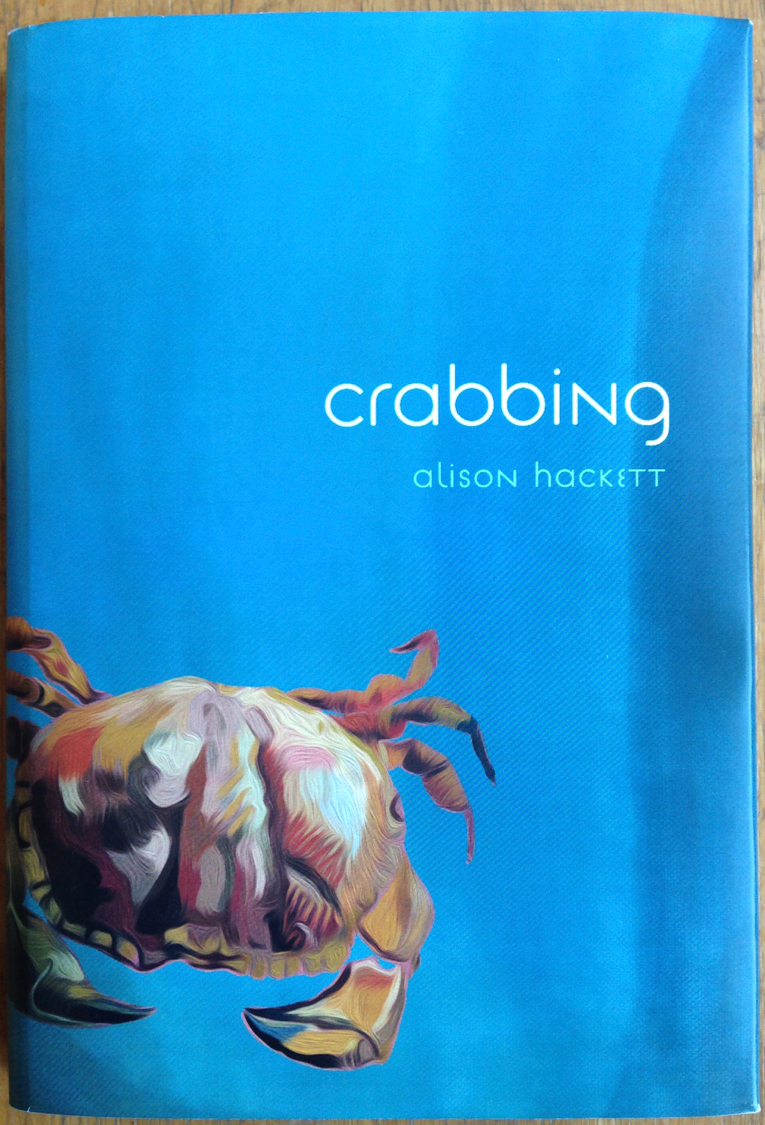

About Crabbing (published by 21st Century Renaissance)

A memoir of love and loss. The voice of a twelve-year-old emerges through the lens of adult eyes in the opening poems. Family and home, people and place anchors this debut collection by the Alison Hackett, author and creator of The Visual Time Traveller.

When the first letters from home arrived for me in boarding school in 1972 they were written in my father’s hand. I only recall one letter from my mother that first term. Years later I realised that she must have discovered she was ill around the time that I had started school. Her world was literally going to end. And she didn’t want to tell me. So, my father wrote to me. I still feel a tug of emotion when I see his handwriting. It was on the brown envelopes curled around the rolled-up Judy, and later, Jackie, comics he sent me every week. No one direction for his script, leaning to the right, to the left, occasionally upright – a strong and distinctive hand with a snappy sign off that always made me smile. He, and his brother, Earle, had edited the student magazine T.C.D. A College Miscellany in the forties Rooted in the classics and Shakespeare, their writing was effortless. Elegance and eloquence peppered with wry humour.

My writing was honed internally. As email communications took off – a time when I was working for the Institute of Physics – I remember sending my first email to the thrilling sound of the dial up connection. After clicking “send” a nervous realisation dawned on me that I couldn’t reach into the machine and pull it back, tear it up, or scratch it out. No second chance with a postal service that delivered at the speed of light. But I hated sending a poorly written email. Why not make it well written, well-argued and force the person reading to sit up and take you seriously? Word Perfect was a dream. We writers could edit-edit-edit exponentially faster. A whole lot easier than a Remmington and Typex. Now, I sometimes edit my poetry online. This is a changed world.

In 1997, I tried out my first writing group while my husband was working in Jena (which was in the former Eastern bloc of Germany). I had three children to mind while he was away for weeks at a time, the youngest being two and a half, the oldest ten. My brain, after seven years as a full time domestic engineer (Mother), was about to seize up. I was running out of steam with the children’s stories at bed time. Writing would tick a few boxes – get me out of the house, meet some adults and exercise my brain.

Reading out my fiction and poetry to a bunch of strangers was nerve racking. The first piece I shared was a stiff short story edited to within an inch of its life. Some people had brought fearfully unedited work complete with typos, spelling mistakes and peculiar grammar – but they had a looseness that was eluding me. Reading back some of my poems from that time I can see the problem: controlled and cool, almost academic, without feeling.

Now, having been through a four-year emotional roller coaster of delayed grief for my mother who died in 1973, I realise that poetry is a type of emotional mathematics. How to meet your readers’ imagination with your imagination, without making them feel queasy or wanting to run for the hills. Finding your voice, your tone, but always with economy. For me, clarity and truth are the most important drivers for any piece of writing.

I had not expressed my grief at the time my mother died. It resurfaced in 2012 as the fortieth anniversary of her death approached. Why did I write The Visual Time Traveller during this traumatic time? It was the most beautiful thing I could create – both for her and for my frightened twelve-year-old self. A creative project with a mathematical structure (twelve facts for every five years and a design to communicate those facts) which suited me. I could escape and immerse myself in it with joy. The poetry which I started writing at that time, was far more directly connected with the grief. Most poems were written through a veil of tears as, for the first time, I faced those feelings of loss and abandonment. I printed these early ones, gave them to family and thrust them at friends. I couldn’t speak.

My father, at that time of that high emotion, wrote to me and said he thought I should publish the poems, poems which must have been hard for him to read. In another letter, he suggested that I get my hormones checked. I had dragged up the past in the most fearful way for him.

The Visual Time Traveller is for my mother, Lesley; Crabbing is for my father, Ronnie. These two publications are to honour them. But they also book-end a very significant period in my life – not only the last four years but that time from the day I turned twelve in 1973 to the present time, the year 2017. I salute you Lesley and Ronnie, my beloved flawed parents.

© copyright Alison Hackett. Posted online 28 June 2017

This article was written was first published online on the writing.ie site here

About Crabbing (published by 21st Century Renaissance)

A memoir of love and loss. The voice of a twelve-year-old emerges through the lens of adult eyes in the opening poems. Family and home, people and place anchors this debut collection by the Alison Hackett, author and creator of The Visual Time Traveller.